Macronutrients, Structuralism, and the Four Humors

In this essay, I will combine three of my favorite intellectual topics: the Middle Ages, the modern wellness movement, and anthropology. Specifically, I will be using Claude Levi-Strauss’s structuralist theory to look at how people think about nutritional decisions.

It is not easy to say how this thing I’m calling “the modern wellness movement” got its start. The discovery of vitamins in the twentieth century could be regarded as an important milestone in the history of nutrition as a subdiscipline of medicine. Diet and exercise have always been understood as components of health, but at some point in the twentieth century, there emerged a counterculture that regarded mainstream pharmaceutical medicine with suspicion and treated nutritional and “natural” interventions as preferable to board-certified Western medicine. Unlike purely religious or supernatural approaches to health (such as, say, the Church of Christian Scientists, who believe medical intervention is a sort of defiance of God’s will), the wellness world combines some of the language and knowledge of scientific medicine with spiritual and moral thinking.

The important distinction I want to make in this essay is between the use of the language of science and an actual scientific understanding of human physiology. In the modern world, we often fancy ourselves to be scientific and rational in our decision making. Many people are familiar with terms from economics, chemistry, biology, and physics and the use of this terminology to explain decisions both public and private. The president can say that he plans to use tariffs to address a trade deficit with an international geopolitical rival, and he reasonably expects the public to understand what he means; at the same time, the voting public may feel as if they do understand what he means and believe they have the knowledge to agree or disagree with what he is saying. We adopt diets meant to induce ketosis or habits meant to improve our circadian rhythm. We listen intently to TED talks addressing learning outcomes of marginalized youth or the most ergonomic way to sit in a chair. We obey workplace policies meant to improve sanitation or stop the spread of contagious viral pathogens. All of this feels like a more comfortable and reasonable way of thinking and explaining our actions than if we were to accuse our neighbor of witchcraft or say that God’s wrath brought a torrential hurricane to a sinful coastal city.

My contention is that understanding the world scientifically is unrealistic or impossible for most people. By design, scientific inquiry is full of uncertainty and depends on a complex understanding of the relationships between evidence and conclusions. A scientist doesn’t “prove” a scientific “fact”, they assemble pieces of evidence that indicate (or fail to indicate) statistically significant relationships between disparate phenomena. A scientist may work for years to develop a deep understanding of a particular issue in their field. The public, generally speaking, accepts the conclusions of scientists on faith, usually with a great deal of simplification and distortion in the process of communication. In this way, the process of the human body expanding muscle fibers following certain kinds of stress using nutrients absorbed in the process of digestion is thought of as “protein helps you build muscle.” This simplification is certainly not wrong, but it also does not reflect a deep scientific understanding of the way the human body works. I say this as someone with one semester of Coursera anatomy—I have no reason to believe my understanding of anything is all that scientific or accurate.

For most people, the process of assimilating the conclusions of scientific research is therefore not about building a nuanced scientific view of reality so much as it is about slotting pieces of wisdom and the language of science into a framework of what is basically magical thinking.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with this, and I am not making this point as a criticism of the intelligence of the “average person”. For one thing, I would argue as Levi-Strauss does that what might be called “primitive magical thinking” is usually highly ordered and empirical at its foundation. The appearance of illogic or ignorance stems from the fact that we are looking at a different worldview with a fundamentally different set of assumptions—what we take as “logical” is always colored by the assumptions of our own worldview. Moreover, I think some degree of magical thinking is necessary for humans to operate in the world. Our minds are not built to fathom the true uncertainty and complexity of the world as it is, so we are constantly developing internal theories based on experience and what we are told in order to produce a “good enough” understanding of events around us. Our knowledge only has to be accurate most of the time—striving for absolute truth would be paralyzing.

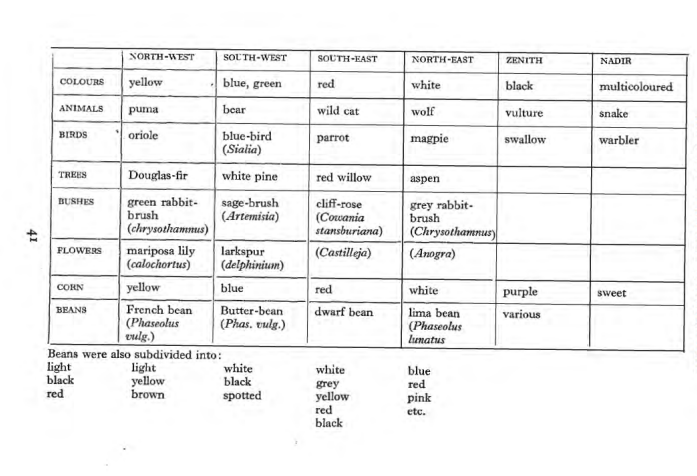

Claude Levi-Strauss was not specifically interested in magic to the same degree that, say, E. E. Evans-Pritchard was. Levi-Strauss’s concern had more to do with the way societies classified things, which tended to influence the use of objects and ideas in rituals and the understanding of cause and effect. It is this classificatory aspect of Levi-Strauss’s structuralism that I think is relevant to nutritional science. Below is chart typical of the kind of analysis Levi-Strauss produced, in this case concerning totemic classifications of the Hopi of North America. I want to stress that this may not be (probably is not) a complete or accurate rendering of Hopi thought as it concerns either the natural world or their society. It is first and foremost a product of Levi-Strauss’s own mind, synthesized from a composite of other, mostly European and Anglo-American, anthropologists.

The accuracy of this representation of Indigenous thought is beside the point for the purposes of this essay. The important thing is the idea of a structuralist understanding of the world: people classify things based on perceived relationships. In the above chart, “puma” is to “bear” as “Douglas-fir” is to “white pine.” The essence that distinguishes a puma from a bear in the world of animals can be translated into the world of trees as the essential distinction between Douglas firs and white pines. The exact nature of these analogous relationships is beyond me. But whenever Levi-Strauss or his colleagues endeavored to try to understand these systems of classification, they usually found them to be based on real experiences and the deep knowledge an Indigenous group possessed of the world around them. People who depended on their environment for survival could not afford to be ignorant about the workings of that environment. Equally important for the purposes of this essay, attempts to systemize these kinds of knowledge for the purposes of an outsider, as in the chart above, can have the effect of disguising, distorting, or omitting the crucial and nuanced bits of knowledge that make the system work as a reflection of the world.

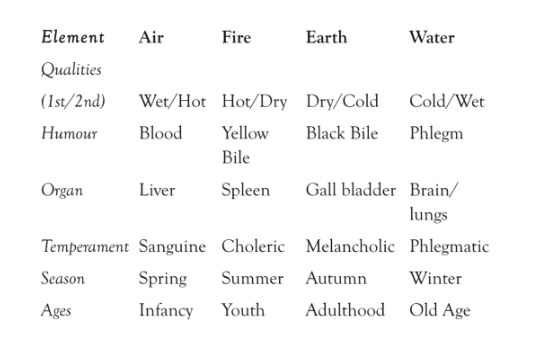

I don’t know if Levi-Strauss or his disciples ever examined the system of relations known as “humorism”. Painting with a broad brush, this was a dominant system of classification many aspects of the natural world in ancient and medieval Europe. I’m far from an expert on this subject—my personal recollection is mostly from reading about medical advances in the early modern period when physicians began to move away from the humors system—so I pulled the following chart from a source located via Wikipedia. The body was believed to contain a unique balance of four “humors”: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Each humor was believed to have attributes outside the human body as well, such as an affinity to a certain “element” or season.

| Nutrient | Protein | Fiber | Fat | Sugar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualities | ||||

| Gender | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine |

| Age | Youth | Old Age | Adulthood | Infancy |

| Pleasure/Pain | Pain | Pain | Pleasure | Pleasure |

| Season | Summer | Fall | Winter | Spring |

| Activity | Anaerobic exercise | Defecation | Hibernation | Aerobic exercise |

It is important to recognize that this system was not based on nothing. Much like the Hopi, European physicians who theorized about the humors started with real experiences and observations. They really saw what they called “black bile” come out of real sick people, and they made the intuitive assumption that this substance, thought naturally occurring, was making these people sick in its excess. This was the logic that led to infamous bloodletting procedures to cure diseases caused by an “excess of blood.”

While their observations may have been real and somewhat sound, it was their attempts at abstraction and elaborate systemization that led humorist theorists to draw increasingly spurious conclusions. In the absence of detailed, reliable data, medieval physicians overstepped their knowledge and drew inferences based, consciously or unconsciously, on pre-existing assumptions about the world. In particular, contemporary beliefs about society and human nature, colored by centuries of religious and philosophical thought, were projected onto the decidedly less familiar non-human natural world.

The previous sentence forges the link between medieval humorism and modern-day wellness theories. The habit of anthropomorphizing and personalizing the non-human world is well-documented in many fields. I am thinking especially of the seminal (so to speak) essay by Emily Martin, “The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male-Female Roles” (1991). In that essay, Martin shows how scientific descriptions of human procreation tend to portray sperm as tiny males playing the active role of suitor or knight-in-shining-armor while ova act like passive damsels-in-distress. To emphasize this point, Martin describes biochemical processes involved in insemination that defy this romanticized framework and, subsequently, tend to be ignored or elided in the physiological literature. Though scientists are not ignorant to the nuances of the insemination process, they are unconsciously drawn to facts that confirm the human suspicion that the universe imitates humanity at every scale.

If professional scientists are susceptible to this anthropomorphizing habit, amateur nutritionists and wellness influencers are undoubtedly more so. How does this tendency manifest? Consider the current “it”-macronutrient, protein. If you haven’t noticed, protein is just about everywhere these days. It’s not just that protein powders are selling at record levels; manufacturers are putting protein in things like chips, cereals, pasta, coffee and water. What is the argument for these additions? Manufacturers and marketers sometimes talk the talk about protein being an essential nutrient for a variety of biological processes, but inevitably, the core of the sell is about having bigger muscles.

When we look at the way protein is marketed—for instance, by the up-and-coming Quest brand – two details stand out. One is the emphasis on quantity. It is not sufficient to simply say that a product contains protein. Most “protein” branded products will lead with a quantity of protein, usually in grams. Like most nutritional promises in the United States, this one is meaningless, because companies are free to set their own serving sizes. Without a “grams protein per grams of product” metric, products can simply use any number they want. More importantly, this emphasis on quantity plays into the idea that more protein equals “more muscle.” That protein is beneficial at all depends on a host of factors unique to every consumer: whether they are exercising regularly, whether that exercise is of the right kind to lead to muscle growth, the current mass and composition of the consumer’s body, and the overall composition of the consumer’s diet, at a minimum. Eating protein beyond what your body can use to build muscle can cause the nutrient to be turned into body fat—something counterproductive to the goals of many exercisers.

The second implication of protein marketing, especially in the latest protein boom, is that protein is for everyone. While some brands refer to athletic activity and present their products as a piece of equipment supplementing a “gym” lifestyle, many others present the addition of protein, without comment, as a simple dietary necessity. In this way, protein additions resemble past moves to add vitamins to breakfast cereals in order to market them as “healthy choices.” Young, old, active or sedentary, everyone could use a little bit more protein.

By contrast, most public health experts believe Americans have no deficiency of protein in their diet. The podcast Maintenance Phase (my favorite source for detailed reviews of public health science) traced the rise of protein as a focus of public health policy in their episode, “The Great Protein Fiasco.” One interesting revelation from this episode is that a lot of the early scientific studies on protein deficiencies in developing countries were influenced by the meat-heavy diets of middle class Americans and Europeans. “If these people are eating less meat than us, it must be they and not us who are wrong”, went the reasoning. This was probably an unconscious bias, but it seems likely that it led some scientists to draw inferences beyond what was strictly evident in their data. Like “The Egg and the Sperm”, we again see human social values being reflected in the conclusions of scientific research.

Where does protein fit into the larger system of popular nutrition knowledge? If protein is the “muscle” nutrient, what are the associations of other nutrients? Previous “it”-nutrients have included fiber, fat, and sugar. Of these, fat and sugar have mainly been implicated in the negative form—”healthy” is equated with minimizing one or both of these nutrients. Fiber, like protein, is seen as a healthy addition, but at the cost of flavor or texture. In this way, a kind of duality emerges: fat and sugar improve taste at the cost of health, while fiber and protein improve health at the cost of taste. Fat and sugar can be used to disguise fiber and protein, but this is often treated as “cheating”. True health, therefore, must involve a small amount of misery. This truism produces a kind of moral spectrum for consumers to place themselves on: how much do you care about health? How “good” do you want to be, and how much “cheating” will you allow yourself in order to fool yourself into making the “correct” choices? Manufacturers can then offer products for everyone along this spectrum, from the die-hard psyllium huskers to the “I can’t believe it’s healthy” protein cookie-eaters.

Each nutrient also provides an orientation for people to align themselves towards or against. Sugar, for instance, can be seen as the substance of children. Stereotypically, children show strong preferences for high-sugar foods; candy, high-sugar cereals and sodas are marketed to and associated with children. Consumption of bitter foods, often in forms specifically negating the above, such as alcohol and coffee against soda or plain oatmeal against Lucky Charms, is seen as a sign of a “mature” palette. Adults who consume things like candy and soda or who add sweeteners to their alcohol or coffee are sometimes regarded as “immature.” At the same time, overconsumption of sugar among children is popularly believed to induce hyperactivity. This phenomenon is not supported by scientific evidence, but it fulfills the expectations of popular wisdom. If overconsumption of “adult” substances, such as alcohol, has adverse behavioral effects in adults, it is logical that overconsumption of the substance of children, sugar, would have an analogous effect on their behavior, and this behavior should be an accentuation of existing childish behaviors: high-energy, impulsive and excitable activity.

We should not forget that sugar also has a strong association with tooth decay. This association is well-supported, but it also confirms our suspicions about the association of sugar with childhood. Losing one’s “baby teeth” is a frequently dramatized experience of middle childhood to early teenage years. Shows aimed at children often have episodes centered on this experience, and the Tooth Fairy is a common figure in the American pantheon of household “helpers” alongside the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus. When a child loses their first set of teeth and grows “adult” teeth, it is seen as a biological sign of the transition from childhood to adulthood, and “coming of age” rites are often celebrated around or shortly after the age when this process is completed, 12 to 13 years old. For an adult to suffer tooth decay as a result of excessive sugar consumption seems to suggest a regression to a childhood malady resulting from “childlike” behavior.

This may seem like a bit of an overanalyzed “just so” story. To provide a contrasting example, are there scientifically supportable associations with sugar that have failed to enter the popular imagination? I was interested to read recently that it may actually be the sugar, rather than the electrolytes, that make sports drinks like Gatorade helpful for high-intensity athletes. The relative “health value” of sports drinks is often questioned due to this high sugar content, but for an athlete in the middle of an endurance-taxing activity, sugar is an essential nutrient in short supply. Again, whether sports drinks are “good for you” is not a static, immutable truth, but a relative one dependent on the context of consumption.

Fat is the nutrient associated with sloth and overconsumption. This is partly due to a semi-arbitrary coincidence of language. In English, the word “fat” can refer to at least three things: a description of a shape that is wide or large; a kind of tissue found in animals; and lipids, the characteristic molecule of fat tissue. Clearly, there is a relationship between these usages, but it is worth noting that the latter, more technical uses were derived from the former. Evidently, as anatomical, biological, and chemical knowledge increased, people took a word with broad applicability and redefined it to refer more narrowly to substances associated with the original meaning. Animals whose shape could be called “fat” were seen to have in common a certain kind of tissue, and that tissue was eventually seen to contain a certain kind of molecule. In an alternate universe, perhaps we would call this substance “thick” instead. (I have no idea if the same kind of parallelism exists in languages other than English)

One result of these etymological developments is that substances not related to fatty animal tissue are referred to as “fats” due to their molecular similarities. Olive oil, avocado oil, and Crisco do not come from animals and have nothing to do with “fatness” in its original meaning. Even many animal-based fats, like butter and cheese, are not inherently connected to an animal’s state of being fat or large. Nevertheless, dietary advice has seized upon verbal and molecular similarities to produce a simple equation: eating “fats” will cause your “fat tissue” to expand and make you “fat.” This equation inspired years of “low-fat” and “fat-free” marketing.

At its most simplistic, this equation imagines that fats are transferred whole from your stomach into your waist. As a matter of fact, all nutrients are broken down into component parts and distributed according to a complex system affected by factors such as genetics, age, hormones, insulin, and energy expenditure. This is not to say that there is no relationship between consumption of fats and development of human body fat. Lipids have more calories per gram than some other molecules, so it is possible to eat more calories of lipids before we feel full. But overconsumption of carbohydrates and proteins can also lead to excess calorie consumption, a necessary condition for the accumulation of body fat. Overall, it seems there is limited evidence for a specific association with any macronutrient other than fiber and weight gain.

The details of this structure of thought related to nutrition may vary from one person to the next and could be debated endlessly. The point I really want to make is that this kind of thinking is a common part of how humans classify knowledge and make it manageable. The Internet-age approach to nutrition, intersecting as it does with scientific medicine and the agricultural food industry, seeks to cast itself as an objective knowledge system rooted in science. Science certainly has a role to play in knowledge production here, but the process by which certain pieces of information are amplified, circulated, built upon, and ultimately become “common knowledge” is, I would argue, colored by a priori associations between food and our social structures.

As an example, let’s return once more to protein. As I mentioned earlier, some of the foundational research establishing protein as a vital nutrient was influenced by the assumption that meat-heavy diets were necessary or better than other diets. I would suggest there is an unconscious structure connecting meat, hunting, and masculinity. Popular culture is obsessed with the “caveman as mammoth hunter” vision of our prehistoric past, even though Homo sapiens probably evolved to eat a diet heavy in fruit and nuts rather than large game animals. It is therefore natural to decide that just eating protein is not sufficient; to be truly healthy, natural, and masculine, one must eat the right kinds of protein, i.e. lean meats. This perception has contributed to an endless parade of dietary trends, studies and stories meant to show that eating the wrong kinds of protein can have negative side effects or simply doesn’t count. A classic example is the “soy boy” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soy_boy/), an Internet-age archetype built on the belief that eating soy feminizes men because soy is high in phytoestrogens (which are, by the way, not the same as the estrogen in the human body). In this case, a scientific observation about the chemical makeup of a product has been combined with the perceived sensitivity and empathy of vegetarians (who may choose to avoid meat out of concern for animal cruelty) as well as the association between violence and masculinity to produce a composite image of male soy eaters as failed men. This image is then turned back onto masculinity more broadly, so that the pejorative “soy boy” may be directed at any man who acts or appears excessively feminine or insufficiently masculine, regardless of that man’s actual diet.

Another example of this kind of process: because of my algorithm’s interest in fitness, health and wellness, I have occasionally come across this genre of video:

A muscular and well-spoken man lays out plates with different foods on them, announcing each one as “30 grams of protein” consisting of a certain food source. “30 grams of protein from eggs” might be placed side by side with “30 grams of protein from peanut butter,” for example. The point is made first by the volume: plant-based sources take up more space, which suggests that they are less efficient if your goal is maximizing protein. The narrator reinforces this point by explaining that meats or animal protein sources have a better protein to calorie ratio, have better bioavailability, and more. My first exposure to this kind of video was actually in the form of a video reply made by another fitness “guy” (?), in which the second man argued that these examples were cherry-picked to favor animal-based proteins in analysis, whereas plant-based proteins with better calorie-to-protein ratios can be easily found. Alas, this rebuttal video seems to have been lost in the algorithm shuffle for all time.

My point is, why do some people feel compelled to make “plants versus animals” content like this in the first place? A similar video that simply discusses protein-to-calorie ratios without the animal-superiority thesis would not gain the same kind of traction. By putting the comparison in terms of something we already “know”—that eating animals is good (or bad)—the video encourages us to pay attention and engage with its message.

These videos serve as an entry point to the “carnivore diet”, which moves beyond protein ratios and demands no consumption of non-meat foods. Like all diet trends, the carnivore diet seeks to guide consumption using a simple set of rules that do not account for the diversity of food production techniques or the individual circumstances of would-be adherents. These diets resonate with people because they confirm a pre-existing suspicion: foods are “good” or “bad” not because of the specific chemicals they contain, but because of some underlying essence emerging from how the food came into existence and what the food represents about the eater. Foods that affirm a positive moral character, whether that is masculinity, pacifism, the natural fallacy, abstention from pleasure, or something else, are inherently healthful to eat because they are deemed good in their essence. Eating “good” means putting good into our bodies, a process that ultimately leads to becoming “good”.