Death Grips, Bob Dylan, Intertextuality, and Old School Cool

The first song on the Death Grips album Government Plates bears the distinctive title “You Might Think He Loves You for Your Money but I Know What He Really Loves You for It’s Your Brand New Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat.” This long and opaque title does not appear in any form in the lyrics of this song. However, any astute listener can realize that the title does have a lyrical source, from the Bob Dylan song “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat.” Here is last verse of that song:

Well, I see you got a new boyfriend You know, I never seen him before Well, I saw him makin’ love to you You forgot to close the garage door You might think he loves you for your money But I know what he really loves you for It’s your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

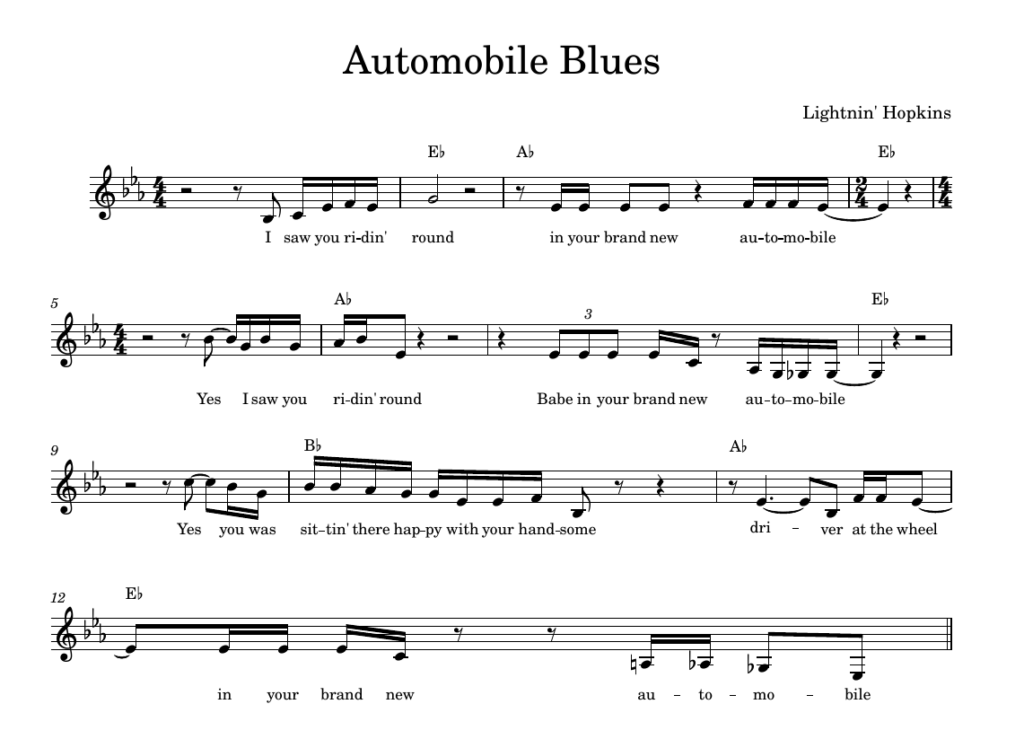

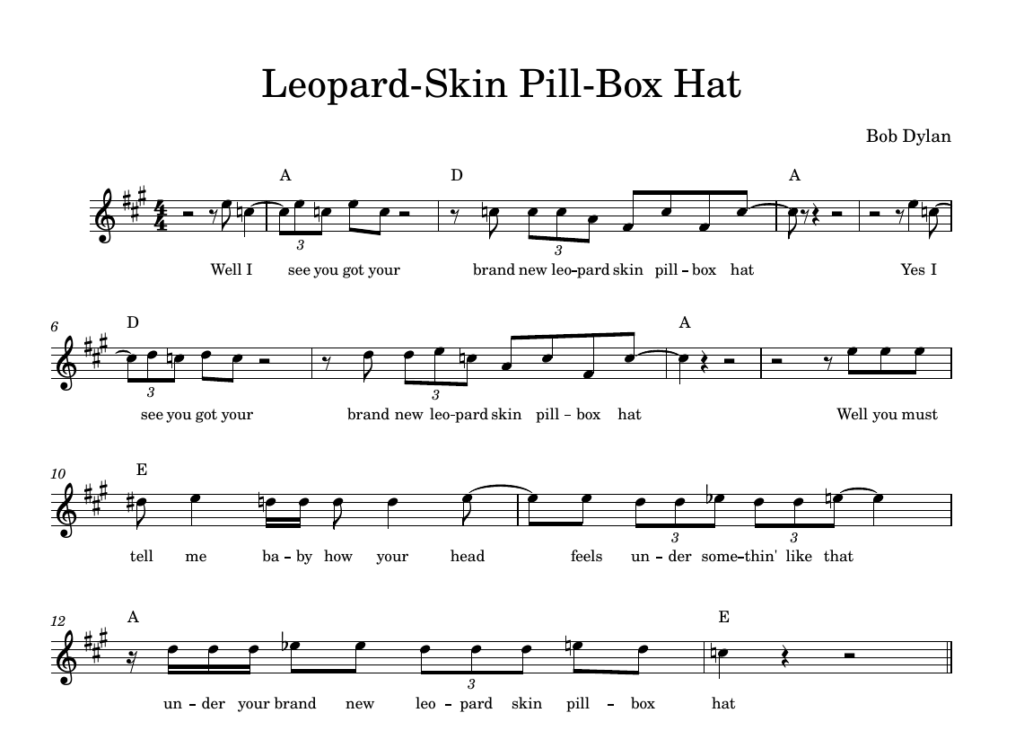

Let us compare the opening verses of the two songs rhythmically and melodically. Note that in these transcriptions, which are mine, the pitch content is mostly approximate, included only for ease of reference, and is not important to my argument here.

Bob Dylan’s song appears on his 1966 album Blonde on Blonde. But this song in turn draws its lyrical and melodic structure from “Automobile Blues”, which appeared on Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins’ 1961 album Lightnin’. Hopkins had previously recorded a different version of the song twice between 1947 and 1950—these recordings were released in 1965 on Early Recordings Vol. 1 and 2 by Gold Star Records, a set that was apparently rereleased as the Gold Star Sessions in 1990 by Arhoolie and is now available under Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. However, Dylan’s song bears much closer lyrical resemblance to the 1961 recording, so I choose to focus my analysis on this version.1 For the record, this is also the version that provides the closest model for covers by Van Morrison and Townes Van Zandt, so it can be considered authoritative simply by virtue of its proliferation among musicians if by no other standard.

To start, I will move linearly through some of the similarities between these two passages. Both begin with a pickup phrase emphasizing the singer’s seeing the person to whom they are speaking. The first two lines in each verse are bifurcated, and the second half after a short pause consists almost entirely of a many-syllabled description of some “brand new” object: “brand new automobile” (six syllables) and “brand new leopard-skin pillbox hat” (eight syllables). The sesquipedalian quality of these descriptions is critical to the tone of these two songs, because their main aim is to poke fun at someone regarded as pretentious or highfalutin beyond their merit. Both singers introduce an interpolated “babe”/”baby” partway into the verse to make clear that the person they are singing to is a woman with whom they share some intimacy or the future prospect of intimacy—this will be important later.

Like many blues songs, the content of the verse can be described as AAB for both songs, with one “call” line repeated twice and then answered by the “response” line over a descending V→ I cadence. But both of these songs add a somewhat rarer additional tag over the I chord, referring prepositionally (“in…”/”under…”) to the fancy new acquisition that is the nominal subject. This brief tag becomes the refrain of following verses, even as the opening line referring to the title object is replaced. The repetition of this tag marks a significant development in blues music, although neither of these songs should be treated as musical firsts in this respect: whereas early blues songs were comprised of numerous, interchangeable tropes that could be traced across dozens of songs and authors (“I woke up this morning…” and the like), the refrains in Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat and Automobile Blues reinforce their coherent, non-deconstructable nature.

In the 1961 version of “Automobile Blues,” lyrical similarities continue. Hopkins writes: “Now your car so pretty baby, will you let me drive some time?”, which Dylan imitates with “Well, you look so pretty in it / Honey, can I jump on it sometime?” The third verse of Hopkins’ song ends with “Everything will be all right baby just about the break of dawn,” to which Dylan responds in his third verse with the opening lyric “Well, if you wann see the sun rise / Honey, I know where.” Hopkins’ third verse also contains the lyric “I just wanna see you let that new car run,” which bears some resemblance to the Dylan lyric “I just wanna see / If it’s really that expensive kind.” More broadly, Dylan makes reference to sexual promiscuity multiple times and specifically refers to vehicular intercourse in his final verse with the line, “I saw him makin’ love to you / You forgot to close the garage door.”

This brings us to the last line of the song and to the title of the opening song of Death Grips’ album Government Plates. Before I move on to that work, I would like to review and establish some of the themes uniting “Automobile Blues” and “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” beyond simple lyrical and rhythmic resemblance. Both songs are overtly about a material object, which as I said is coded as pretentious. The word “brand new” establishes this clearly in both songs, but there are additional clues that suggest the same meaning. “Automobile Blues” makes reference to a “handsome driver” as well as a “chauffeur”, and the two versions recorded between 1947 and 1950 also include a verse about “Your face…tinted with powder / Your lips all full of rouge.” “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” talks about the hat being “really that expensive kind” and of course about the new lover who ‘doesn’t love her for her money.’ Dylan adds insult to injury by insinuating that the hat fails to live up to its own pretention and is in fact ugly, like a “mattress [balanced] on a bottle of wine” or a “belt wrapped around my head.”

The more essential thrust of both songs is the portrayal of a jealous lover reacting with venom to his former or current lover’s simultaneous infidelity and class ascension. Not only does she have new possessions, but she is also surrounded by high-class professional men (chauffeurs or drivers, doctors) who have replaced the narrator, a presumably low-class, uncouth and potentially unfortunate young man—this being the default position of most blues songs—and now greedily withhold her from association with the narrator.

Let us turn now to the Death Grips song, which I will abbreviate as “You Might Think.” Like many of the band’s songs, MC Ride’s lyrics here are opaque and cryptic. Unlike Hopkins’ and Dylan’s songs, there is no obvious resemblance between these lyrics and the Dylan song referred to in the title. The chorus points to a theme of death, and even a state beyond death towards total annihilation:

Get so fuckin’ dark in here Come, come fuck apart in here I die in the process You die in the process Kettle drum roll hard shit Fuck I said fucker don’t start shit Come, come fuck apart in here, I Come, come fuck apart in here, I

Perhaps the closest the song comes to a meaningful resemblance to the first two songs discussed is in the second verse: “Fear, you wear it well, Mademoiselle / Here’s to your destiny / Hysterics scream help / Don’t worry, in a few you’ll all be somewhere else.” “Mademoiselle” suggests, vaguely, the same kind of pretentiousness as “brand new” and “expensive”, although the coding of French titles with affluence might be limited to certain parts of the United States. The extreme violence towards women in MC Ride’s lyrics seems like an extension of the venom and vitriol in Dylan’s song, which itself is heightened and exaggerated compared to Hopkins’.

The lyrics being, mostly, no help at all in understanding MC Ride’s allusion to Dylan, it is left to us to speculate more broadly about Death Grips collective discography. This is not the only time Death Grips has used music and culture from the mid-twentieth century as a point of reference. “Beware” the opening track of the album that constitutes many listeners’ introduction to the band, Exmilitary, begins with about a minute of audio from a recording of Charles Manson. From the same album, “Spread Eagle Cross the Block” samples Link Wray’s “Rumble” (1958), “Klink” samples “Rise Above” by Black Flag (1981), and “Culture Shock” uses David Bowie’s “The Supermen” (1970). “I Want It I Need It (Death Heated)” includes the line “Gonna have to do this shit Jim Morrison style.” “Inanimate Sensation” on The Powers That B makes reference to Axl Rose, Slash, Rick James, the Beatles’ song “Mean Mr. Mustard,” and Lady Godiva, a possible reference to the 1966 song by Peter and Gordon as well as the medieval noblewoman herself.

Immediately, it is clear that Death Grips uses samples and allusions to comment on their original songs. At the very least, they seem to tacitly acknowledge that their lyrics are nearly impossible to decipher on their own; a well-chosen sample, often at the beginning of a song, points the listener toward the intended meaning of the song as a whole. Manson on “Beware” suggests menace as well as preternatural human control (of others as well as the self, although this may be interpreted more as a delusion than a reality); “Rise Above” points to political rebellion in response to the police brutality described in “Klink.”

The choice of era (predominantly 1960-1980) is sometimes connected with the theory that Exmilitary chronicles the life and internal struggles of a Vietnam war veteran, but the fact that references from this time period occur on other albums and seem to outweigh contemporary twenty-first century references would suggest that the “old school” is somehow more critical to Death Grips’ collective discography than just one concept album.

Internet culture is another major area of reference for Death Grips. Exmilitary includes the samples “you need to vibrate higher” on “Culture Shock” and “if you’re delusional your call will be transferred to the mothership” from “Thru the Walls,” both taken from videos primarily distributed via the Internet. The Money Store includes two songs, “I’ve Seen Footage” and “Hacker,” referring to Internet-based purveyance of conspiracy theories and electronic hacking respectively.

The combination of audio samples and lyrical allusions to produce dense intertextualities is obviously not unique to Death Grips. In fact, in terms of technique it places them squarely in the territory of hip hop music, and they are frequently referred to as a hip hop group (sometimes “experimental”) by music journalists. But in terms of the source material for their intertextuality, I would argue Death Grips is a decisive departure from hip hop conventions. During the first thirty or forty years of hip hop history, artists in the genre primarily pulled from previous hip hop as well as rhythm and blues, funk and soul music (as well as African American culture more broadly) for its samples and references. Moreover, hip hop has always involved an ongoing artistic conversation between contemporaries. Even outside of overt diss track exchanges and live rap battles, it has been common for artists to make reference to other contemporary artists both competitively and collaboratively, paying respect and derision when each is deemed appropriate. Death Grips, by contrast, seems to want to exist in a world where other rap artists don’t exist and the whole of hip hop didn’t happen. Instead, they treat artists of a bygone era, such as Bob Dylan and Jim Morrison, as contemporaries and musical co-conspirators. While the music of Death Grips is indisputabely modern, it is also aggressively anachronistic and dedicated to the “old-school cool.”

Their anachronism, combined with their interest in Internet culture, combine to create a pervasie sense of timelessness throughout Death Grips’ discography. The culture of the Internet–and those who grew up treating it as a “third place” akin to the skate parks and pool halls of previous generations—is notorious for flattening the time spans of history, treating the clothing, music, art, and entertainment of all past generations as equally viable for reuse and remixing. While newspapers and broadcast—the media of the twentieth century—necessarily carry with them a sense of timeliness and rapid decay, everything on the Internet is presented as occurring in an eternal simultaneity. The memes of tomorrow are as likely to feature movie quotes from 1970 or photographs from 1990 as they are songs from 2023. The Internet insists on portraying the world as post-diachronic. By aligning themselves with this post-diachronic, timeless world, Death Grips presents itself as categorically distinct from conventional hip hop. Whereas hip hop, a quintessentially late twentieth-century genre, is always timely and up-to-date, the music of Death Grips in the early twenty-first century is anachronistic and ultimately out of time.

- Hopkins’ song draws significant influence in turn from the song “Too Many Drivers,” recorded by Big Bill Broonzy in 1939. The historians at Wikipedia claim “Automobile Blues” is simply another version of “Too Many Drivers,” but this is in my view a real stretch of the musical work-concept as it applies to songwriting. To begin with, every publication associated with Hopkins’ recordings refers to him as the author of “Automobile Blues.” Both songs use the idea of “too many drivers” at the “wheel” as a double entendre for sexual promiscuity, but beyond this they have almost no direct lyrical similarities. Aside from using a completely different set of lyrics, the lyrical structure of “Too Many Drivers” is fundamentally different. Hopkins song follows the pattern AABC, with a repeated first line and a tag refrain C that is the same in each verse; Broonzy’s song, on the other hand, mostly uses two different rhyming “call” lines and repeats the entire “answer” rather than just the tag in three of the four verses. While “Automobile Blues” repeatedly refers to a “brand new automobile,” “Too Many Drivers” refers instead to a “pretty little automobile”, a description also used in Hopkins’ own recording entitled “Too Many Drivers,” which uses a whole different set of lyrics from either Broonzy’s song or “Automobile Blues,” but which bears more similarity to the original “Too Many Drivers” than any recording of “Automobile” or “Automobile Blues.” If we are to accept that “Automobile Blues” is a version of “Too Many Drivers,” then we must also accept that “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” is another version, rather than an original song, because it is much more similar to “Automobile Blues” than the latter is to “Too Many Drivers.” This is not to mention the dozens of other songs throughout twentieth-century that use cars and drivers to similar metaphoric effect. Is Bruce Springsteen’s “Pink Cadillac” just another version of “Too Many Drivers”? Or is it easier for us to assign authorship to white men in the late twentieth-century singer-songwriter tradition than Black men in the early twentieth-century bluesman tradition…? But I don’t have time to get into that. ↩︎